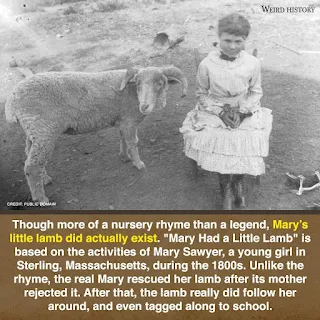

The True Story Behind “Mary Had a Little lamb.

The

nursery rhyme, which was was first published in 1830, is based on an

actual incident involving Mary Elizabeth Sawyer, a woman born in 1806 on

a farm in Sterling, Mass. Spoiler: its fleece *was* white as snow.

Birth-place of Mary Sawyer and the little lamb. Sterling, Mass.

Photography Art and Picture Collection, The New York Public Library.

The

nursery rhyme, which was was first published in 1830, is based on an

actual incident involving Mary Elizabeth Sawyer, a woman born in 1806 on

a farm in Sterling, Mass. In 1815, Mary, then nine, was helping her

father with farm chores when they discovered a sickly newborn lamb in

the sheep pen that had been abandoned by its mother. After a lot of

pleading, Mary was allowed to keep the animal, although her father

didn’t hold out much hope for its survival. Against the odds, Mary

managed to nurse the lamb back to health.

“In

the morning, much to my girlish delight, it could stand; and from that

time it improved rapidly. It soon learned to drink milk; and from the

time it would walk about, it would follow me anywhere if I only called

it,” Mary would later write in the 1880s, many decades after the

incident. And, yes, the lamb would indeed follow her wherever she went

and did have a fleece as white as snow.

Sometime

later, it’s uncertain exactly when, Mary was heading to school with her

brother when the lamb began following them. The siblings apparently

weren’t trying very hard to prevent the lamb from tagging along, even

hauling it over a large stone fence they had to cross to get to Redstone

School, the one-room schoolhouse they attended. Once there, Mary

secreted her pet under her desk and covered her with a blanket. But when

Mary was called to the front of the class to recite her lessons, the

lamb popped out of its hiding place and, much to Mary’s chagrin and to

the merriment of her classmates, came loping up the aisle after her. The

lamb was shooed out, where it then waited outside until Mary took her

home during lunch. The next day, John Roulstone, a student a year or two

older, handed Mary a piece of paper with a poem he’d written about the

previous day’s events. You know the words:

Mary had a little lamb;

Its fleece was white as snow;

And everywhere that Mary went,

The lamb was sure to go.

It followed her to school one day,

Which was against the rule;

It made the children laugh and play

To see a lamb at school.

And so the teacher turned it out;

But still it lingered near,

And waited patiently about

Till Mary did appear.

The

lamb grew up and would later have three lambs of her own before being

gored to death by one of the family’s cows at age four. Another tragedy

struck soon after when Roulstone, by then a freshman at Harvard, died

suddenly at age 17.

Here’s

where the controversy begins. In 1830, Sarah Josepha Hale, a renowned

writer and influential editor (she’s also known as the “Mother of

Thanksgiving” for helping making the day a holiday), published Poems for

Our Children, which included a version of the poem. According to Mary

herself, Roulstone’s original contained only the three stanzas, while

Hale’s version had an additional three stanzas at the end. Mary admitted

she had no idea how Hale had gotten Roulstone’s poem. When asked, Hale

said her version, titled “Mary’s Lamb,” wasn’t about a real incident,

but rather something she’d just made up. Soon the residents of Sterling

and those of Newport, New Hampshire, where Hale hailed from, were

arguing about the poem’s provenance – something they continued to do for

years. In the 1920s, by which time both Mary Sawyer and Sarah Hale were

dead, none other than Henry Ford, the man who revolutionized the auto

industry, leapt into the fray. The inventor sided with Mary’s version of

events. He ended up buying the old schoolhouse where the lamb incident

took place and moved it to Sudbury, Mass., then published a book about

Mary Sawyer and her lamb. In the end, it seems the most logical

explanation is that Hale simply added the additional stanzas to

Roulstone’s original (which she’d probably gotten wind of at some

point).

But

wait! There’s a third version of how the Mary and her lamb story came

to be. Across the pond in Wales, Mary Hughes, of Llangollen,

Denbighshire, was credited with being the subject of the nursery rhyme

supposedly penned by a woman from London by the name of Miss Burls. The

only problem with the U.K. version of events is that Mary Hughes wasn’t

born until 1842, twelve years after Hale’s poem was published.

In

the end, the nursery rhyme took on a life of it’s own after it was set

to music. It became wildly popular beginning in the mid-1800s. The poem

even became the first audio recording in history when Thomas Edison

recited it on his newly invented phonograph in 1877 in order to see if

the machine actually worked. It did. Listen to it here. Back in

Sterling, Mass., they continue to celebrate Mary Sawyer. There’s a

statue of the famous lamb in town, and a restored version of Mary’s home

(the original was destroyed by a pair of arsonists back in 2007). Her

descendants continue to farm the land that gave birth to the most famous

nursery rhyme of all time

کوئی تبصرے نہیں:

ایک تبصرہ شائع کریں